Mr. Ali informs us on book publishing in Africa and his experiences in Europe in that field. When we shift themes, Mr. Ali unfolds his perspective on other matters like the digital revolution, secessionism, xenophobia, modern history, the role of governments, politicians, and intellectuals against an African-European backdrop.

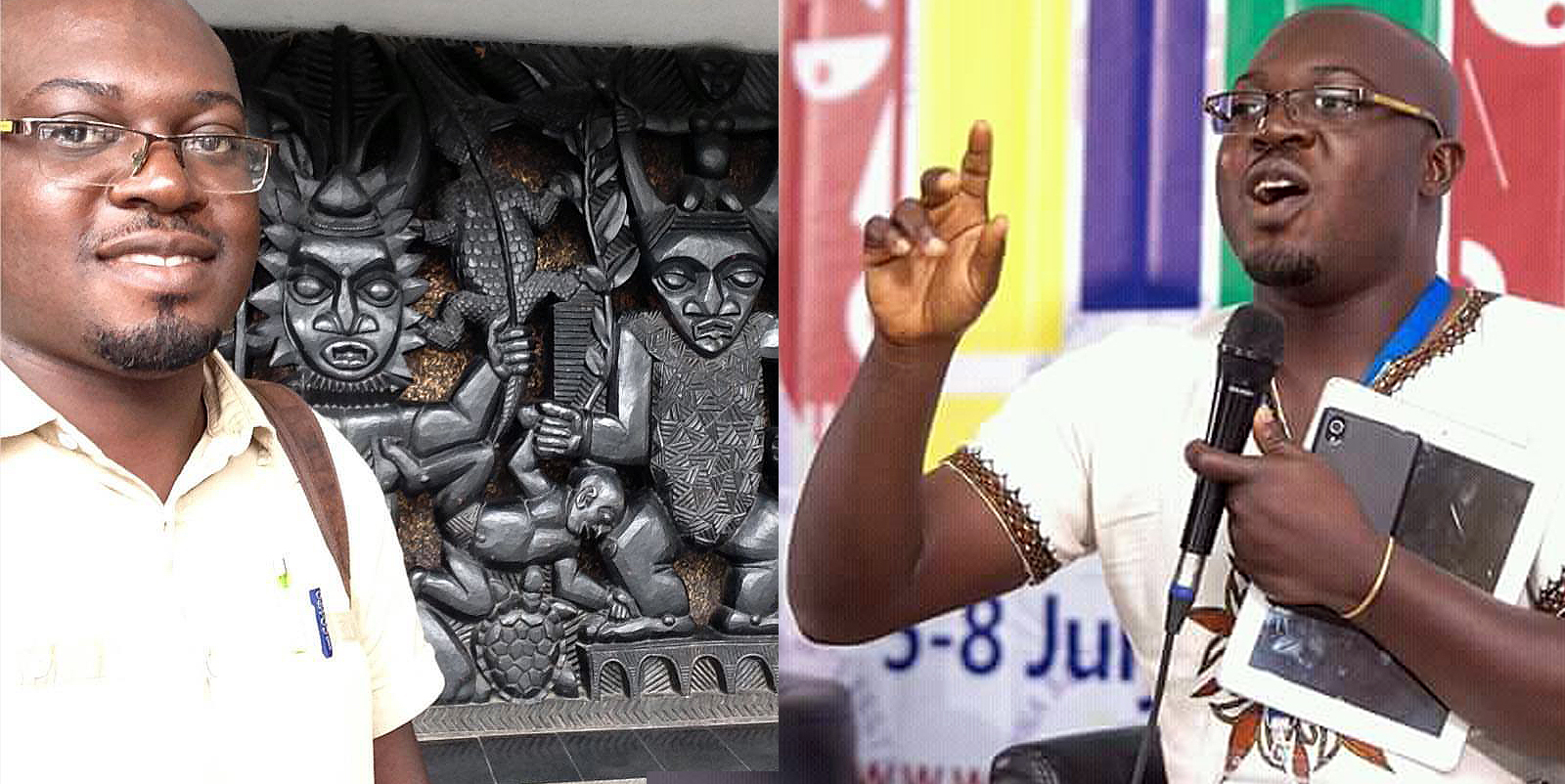

Personal Perspectives is an interview series, a platform on which we invite people to share their perspectives on issues that affect us all. UbuntuFM was privileged to sit down and speak with Richard Ali, book publisher, and lawyer from Nigeria.

Mr. Ali, dear Richard, how are you doing? Thank you so much for the opportunity of allowing us to conduct this interview with you. Could you tell our readers a little bit about yourself?

I was born in Kano in the early ’80s, Kano is one of the biggest metropolises in Nigeria. Being the five-hundred-year-old seat of an emir and before that, sultans who style themselves as Sarki or King, Kano long predates Nigeria the country. My family is from central Nigeria and we moved to the resort city of Jos from Kano when I was quite young and I grew up there. So, I’ve always been a city boy.

Jos was a cosmopolis growing up, people from all over the country had made it home for decades, for its cool weather—it sits atop a plateau of the same name—and its easy going people. I’ve always identified myself as being from Jos.

I studied law at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, was called to the Nigerian Bar and later moved to Abuja where I currently live. Important to me is the sense of loss of the city of Jos. From about 1999, when there was a transition to civil rule, the city was wracked by sectarian crises dubbed “ethnoreligious” and its cosmopolitan essence was lost. What it was before, and its loss is quite central to my identity and to my writing. I deal with it in my 2013 novel, City of Memories.

As a publisher, you must have a keen sense of the publishing business in Nigeria. Where does Nigeria stand when compared to other African nations and for instance Europe or other regions around the world?

Publishing in Nigeria is a tricky undertaking.

This is because of certain structural issues that have to be overcome, leading to inefficiency. I like to think of publishing as a labor of love. I’ll tell you why. Regarding other African countries, each has its own peculiarities, their own challenges. For example, my Rwandan friend Louise Umutoni of Huza Press had the first objective of generating new Rwandan stories and she did this through a wildly successful short story competition. She has however moved on to solving the distribution issue through her new Huza Books online book order platform grafted onto the Huza website. In Kenya, Magunga Williams set up the Magunga Bookstore to address the accessibility issue and is doing a fantastic job. Perhaps only in South Africa is publishing so robust as to be called an industry proper?

In Nigeria, there are two major problems—the issue of costs, which affects pricing, which affects who can buy your books, and on the other hand the issue of marketing and distribution.

Costs are extremely high and, at an average of between $6 to $10 dollars per title, it exceeds the budgets of the average Nigerian. The minimum wage is about $50 a month. The reason for these high costs is that 80% of printing consumables are imported, from paper to ink to gum, and with the precarious state of the naira, dependent on the oil market, costs add up. A book that should sell multiple of that has difficulty shifting a thousand copies. We don’t have book distribution networks or chains either, and this adds to the costs. In effect, there is precious little margin left for marketing, and this feeds the cycle.

Europe has a very sophisticated book market. I was at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2014 and was able to study and observe it. Distribution is easy as there are chains that own or co-opt outlets country-wide, in some cases, there are even pricing ranges to ensure that books are not sold below a certain price so that the publishing industry can take risks and thrive. Marketing is very sophisticated too, with specialists every step of the way.

I think Syria used to have a similarly sophisticated market until the West decided to go and make a mess of that country.

If Nigeria and most African countries can solve the problems of cost and pricing, and the issue of marketing and distribution, we have the numbers to out-sell the West in terms of copies sold. And, there is no doubting that the creative content is widely available, as people like Huza Press and Beverley Nambozo Nsengiyunva’s, Babishai Niwe Poetry Foundation’s BN Poetry Award, and the Jalada cooperative have shown conclusively. The BN Poetry Award is run out of Kampala while Jalada is based in Nairobi These are all concrete African interventions. I should also mention the CACE/Writivism Festival, also in Uganda, and Rachel Zadok’s StoryDay Africa in South Africa which through workshops and curation have generated really consequential African stories.

Digital publishing has been an ongoing trend for years now. The introduction of e-readers and online publishing platforms must have changed the business you are in quite dramatically. How do you see this change? Has book publishing become more challenging or do online and global distribution networks offer more opportunities to you?

This is a positive change. In Nigeria, we have a platform called Okada Books set up by a young man named Okechukwu Ofili. It’s a mobile app that allows users to read on the app and he’s gotten about half a million users already. Really impressive. I met him some weeks ago at the Lagos International Poetry Festival and he is already well known to Azafi, my partner at Parresia Publishers Ltd.

We talked about creating a partnership on a poetry platform I control, as well as for another literary platform which I am a member. As a creator and a publisher of original content, I will go wherever the market is. If the market is at the street corner, I’ll be there; at a book fair in Jo’burg, well I’ll run the figures and try to get there. What more if the market is inside mobile phone software? The point is to make sales, create value for one's brand, provide revenue for our writers, and to be able to take more risk on non-mainstream voices needing a platform.

Parresia embraced the digital world quite early. In the first instance, not long after we started, it was a partnership with an e-commerce platform called Konga.com to help address the issue of distribution. They had a national distribution system, reasonably cheap, and we had books to distribute. So we set up an e-store—one of the very first booksellers on the site. We also have one on Jumia, Konga’s major rival in the Nigerian market.

Later on, we met with Gersy Anumufo and went into digital fully with a partnership with her London-based Digital Back Books which is a library lending service that has grown in leaps and bounds in the three years we have worked together. Just a few weeks ago, Azafi and I okayed a contract with World Reader, another digital platform.

So, digital is a new way to do what publishers have always done. I see it as an opportunity to match changes in lifestyle and the way text, and literature, is consumed. It also expands the publishing industry and makes partnerships inevitable. It’s quite exciting working with these new players towards our shared objectives.

Since the advent of the internet, access to information has ‘globalized’. People from across the globe are able to access the latest information in the blink of an eye. They are able to inform themselves about subject matters that may have been out of reach to them, prior to the internet. What is your take on this? Is it all for the better?

Interesting question. Yes, it is a good thing that accesses to information has been globalized and you can know what is going on in Krychaw now with the aid of a search engine. The mantra of liberalism is that more is better, no? So, one is tended towards thinking ah, this is good.

But what about the quality of the engagement? What does it mean to have access to millions of websites and so much information when our attentions spans last only a few seconds? To have information is a great thing, but when that information is assessed superficially, is that so good, is that not dangerous even?

There is the reality of too much information, there is the reality of information fatigue. I think that an unintended consequence of the information revolution has been the democratization of thoroughgoing but very confident ignorance on the one hand and the rise of corporate organizations ranging from Google to Facebook to CNN who thrive on disinformation and propaganda—creating false emphasis that, when read, has the semblance of an independently arrived at the thought which is anything but that.

The issues are everywhere, we see it in the brave activities of Julian Assange and WikiLeaks, we see it when media outlets loop news with subtle agenda 24/7, we see it when no matter on which device I launch or open Facebook, it starts with the same content some algorithm has decided I should want to see no matter what. When Donald Trump makes his rants about “fake news”, we dismiss him for being infantile and hypocritical, for he is a keen promoter of it when it serves him. But the nexus of all of this is a pernicious sort of disinformation that has thrived just as access to information has become more open. Irony? Catch 22? Inevitability?

See, I was one of the young people who came of age in the environmental movement of the 90’s—Kyoto Protocol, the Rio Accord, and so on. Starry-eyed and optimistic. But in time, you learn there is much more at stake and that your honesty can fit into a politico-corporatist agenda framework other aspects of which you are vehemently opposed to, aspects that are in fact dangerous to your being.

The genie has left the bottle, but sometimes I wonder if it is not better to merely have all the information you want which is relevant to you? You, individual, decide this. Not Mark Zuckerberg or some executive at CNN. [#NetNeutrality]

How can we put the human being, in humanist terms, back at the center of the information revolution, is the question? With the talk of AI and the mega-corporations that provide it, is this not too late?

Lastly, there is of course the issue of the media trial and its attendant reality TV type dramatizations of opinions and remorse. Forgive this African but the West is looking increasingly like a continuum of tribes, this time based on what they call “communities”, and with tribes, witch hunts are as natural as is blood feud and ordeals. I see this every week and I am worried. But this is our brave new world.

In recent years we have been able to observe a trend that counters the process of globalization that has been going on since the late ’90s. ‘Brexit’ most notably, but nationalism in general and xenophobia, in particular, seem to be on the rise again. Are we correct in these assumptions? How do you see this?

It’s funny. What we are seeing is the crisis of the concept of the nation-state on the one hand and an interesting partial vindication of the Marxist thinkers.

The partial is crucial. I mean in their theory of class struggle and society being organized by the forms of production. The rise of private property and capital was seen as the harbinger of great inequality such as what we see today, to this extent they were right. There is nothing benign about capitalism, welfarist thinking always was a rather thin veneer that has worn off. Now, in today’s stark inequality, elites thrive. The idea of the 1% is indicative of this.

But even amongst the elite, there is only so much to go around. There is only one earth, for now, and there are only 192 states. So, you have elites splitting states so that there are more fractions to extract from. The Marxists thought that the socialist revolution would overthrow this capitalist world and replace it with socialism and then communism. But look out the window? Is capitalism dying anywhere?

It is we who will die. Brexit exists because a certain business elite in Britain felt they could get no more from Europe and there was more to be exploited, for them, if they were left to scavenge an insular Britain by themselves. And, overarching both this is the irremediable place of post-structuralism in public thinking. These are the ingredients.

Now, the nation-state with nationalism at its core. When the nation-state was conceived, we must look at it as being a sort of virus aimed at the multi-ethnic state which, in paradox, served the aims of the colonialism that followed. The intent of the nation-state was to break up polities like Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman empire, as the two biggest examples, which were based on the idea that different peoples could live as citizens of one state. Consider the Austrian and the Ottoman states as proto-EU-type states.

Nationalism was the sticks of dynamite that was placed on the stitch work of these old types of states, along the veins of issues of social mobility and privilege, to blow them all up into nation-states that were, by definition, exclusivist. Detonation over, you now had said five states in the place of one and each, of course, needs its own extractive, exploitative elite.

Where “what makes us us” could not be found, it was invented. Take Italy for example, Venetian territories, parts of Austria-Hungary, and others were cobbled together into something called Italy, a nation-state, for which a language, an updated Tuscan dialect, had to be held up by the force of law as the national language. Singularities have always been the fruits of the nation-state, a rejection of diversity. This is because nationalism is at its heart and nationalism is, by definition, exclusivist.

The bloom of cancer of this came early and quickly, with two world wars where these recent nationalisms faced each other and comically gassed and shot each other’s kids by the millions. As early as 1918, the West saw the error at the heart of the idea of the nation-state and sought to assuage it by the League of Nations. At the same period, capitalism was coming to its own, and between nationalism and capitalism, we had a second war. So, the European community and the idea of Europe were brought back, the idea being a multi-ethnic state indistinguishable from saying Austria-Hungary or Ottoman Turkey.

If the EU is where you were going, why didn’t you let the Ottomans and the Austro-Hungarians be? Supra-states like the EU is intended to be, are patching of the cancer of nationalism inherent in the nation-state. But how do you patch something viral? The idea that people like “us” who have “something” in common should be a political basis had seeped into peoples and would-be elites rubbed their hands together for the pillage to come. The Cold War kept today’s chaos in check a bit. Soon after that ended, the nation-state and its twin nationalism started replicating and we had Bosnia and Kosovo.

Today’s xenophobia is not new, it is inevitable, it has only arrived at its own time.

Add to this the dominance of post-structuralism everywhere, the acceptance of it as being an apparent guide to each person’s engagement with his environment—from the academic to the street hawker. To my mind, this thinking, which has at its roots the rejection of structure, objectivity, and certainty did what nationalism did to states to individuals. A single man is suddenly a god because God is dead, except that there are several billion men.

Poststructuralist thinking further fractionated the fractions nationalism had created and, more, opened the door for endless fractionalizing. The idea of complementarity has long given way to the singularity which becomes exclusivity, yet, interestingly, these new exclusivities consider themselves to be “communities”. Do you see the chaos? Can a community that is exclusivist be in fact a community, does a community not in fact mean diversity? Yet look at the labels, what they mean and what they have come to describe.

Hence the chaos of the West today. When Nigel Farage or his counterparts in Europe perform xenophobia and uphold nationalism and admire fascism, they must be seen as expressions of the complicated nexus between the idea of the nation-state, advanced capitalism, and post-structuralism. I think it is inevitable.

The way out is to return to the old ways of state management. I’ve got no dog in the fight but the idea behind the EU is a good one that should win, but to win there must be structure.

Germany is the most likely to give that structure but it, for its own recent historical reasons, is wary. But if we do this, what do we do about capitalism and post-structuralism?

Most recently secessionism came into view again, when affairs in the Catalunyan region of Spain took the world’s headlines. Being from Nigeria you may have followed these events with more than average interest, as Nigeria is facing a similar issue in the region of your country we have come to know as Biafra. Is that a fair assessment?

This follows from my last response. Nationalism is a virus, the idea of the nation-state is a virus. The exclusivity that separationists seek is endless, like an onion or a babushka doll and there will always be more reasons to hack at communities and cosmopolises until each man stands alone, smug and satisfied in the center of a pile of bodies.

It can be gathered that the Biafran people are driving for secession from Nigeria in a similar fashion as the Catalunya. Is this correct? Are these similar movements? If not, could you please shed some light on what this current trend is all about?

They are similar and yet they are dissimilar. Strange but true. The similarity is in that they are both separatist movements and that the proponents of both are afflicted by the virus that is nationalism. I have already set out why I think this is unfortunate, why I think this is a virus. What these separatist agitations do is to understand human psychology, the ease with which the human being creates binaries, and turn this psychology against the human being by formulating their political appeal in terms of “us” and “them”, that is step one.

Step two is switching “us” and “them” into “us” against “them”. This second step is important because this is the only way separatists can gain power. They want power, they cannot articulate a broad-based ideology, so they balkanize a polity in order to access power easier. It is the same thing in putative Biafra. At the center is the elite seeking power and willing to let others kill themselves so they get what they want.

The dissimilarity lies in that there is at least a distinctive Catalan culture and history on which an argument may be made, and, I read, 800-year-old Catalan history of identity. Also, there is a conquest and mapped-out struggle for realization by the Catalans. So, there is that as a basis. To this basis, we address the question:

What is it that the Catalonians want in a new Catalan State that they do not have in Spain today?

Other than the political and business interests of their elite? What is it, broad-based autonomy? Language? Culture? What is it? In the case of Biafra, no such basis exists. No Biafra exists in history. And if we are to scale Biafran identity down to the Igbo ethnicity, the idea of an Igbo people was created only recently, perhaps in the memory of people even still alive.

The most striking feature of the Igbo people is their republican nature, the absence of centralized authority except in certain marginal cases. It was not until the British imposed Warrant Chiefs that any semblance of centralized authority came to being, and even these were met with the saying that “the Igbo have no kings”—every man, every compound, every lineage group, every village governed themselves as they saw fit. There were a shared language and some shared religious beliefs but no state institutions or shared cultural practices or political structure.

It was the British that, in imposing Warrant Chiefs, set the stage for the creation of the idea of an Igbo people as exists today. So, in this, Biafra is entirely dissimilar to Catalonia.

Now, further on Biafra. The European idea of nation-states inspired the hasty creation of several new types of people in the early 20th century—Hausa people, Igbo people, Yoruba people, and so on. Revisionisms and reinterpretations were undertaken by emerging political elite classes to argue that these people in fact have existed always, both amongst geographies where states existed and those, like southeastern Nigeria and to an extent, central Nigeria, where states did not exist. This assertion is, of course, only fanciful foundation work.

In the dislocations following the Second World War, the British had to give independence to her colonies, including Nigeria, and self-governance was declared and power handed over to the ethnic elite who had emerged in the three regions—northern, western and eastern—of Nigeria through the instrument of political parties and elections. After a long process of negotiations, independence was granted to a new country called Nigeria, comprising three near-autonomous federated regions.

On January 15th, 1966, predominantly Igbo putschists led by Igbo officers turned on their senior officers and killed them as well as the political leadership of the north and the west. The coup failed from the actions of officers from the north who escaped the dawn killings in Lagos, and in Kaduna, it failed when the sectional nature of the killings became known. The GOC of the Army then put down the coup, though some have accused him of being complicit in it, but at the cost of his taking over power from the rump of the elected Federal government. He was Igbo.

The demand of the north particularly was for the putschists to be tried for their crimes. He failed to do this. In July of that year, there was a bloody counter-coup led by the northern officers whose region had borne the brunt of the January coup. What was the purpose? They wanted to secede. Convinced not to, they assumed Federal power. There were killings of Igbos in the north, that is for sure. The East declared their independence, the rest of the country refused. And there was a civil war which the Federal side won conclusively. When Biafran separatists speak today, it is to this Biafra that they allude.

My being against separatism, whether in Catalonia or Biafra, is premised on the appeal to a curious type of xenophobia that underlines them all.

This type of xenophobia is a latency, any group at all can foment it. Any group of the elite can stir the cauldron and, when they succeed, achieve power and office and loot. It’s the basic human psychology of binaries being manipulated. But, after you have opened this vein up, you cannot turn it off. How do you turn it off again? The basis of separatism being things as arbitrary as ethnicity, or language, being arbitrary, how can it not devolve to just as arbitrary basis for further separatism such as, perhaps, geography, height, skin complexion, or ranges in the length of noses? This last, where have we seen it before? Rwanda.

I am not in support of separatism because I think the nation-state idea is a virus and I am a believer in multi-ethnic states.

I do not support the balkanization of multi-ethnic states because it can only lead to further separatisms and these, other than not, are done in blood. The blood of young people. And yes, I do not like separatist movements because, while they pose as heirs of post-structuralism, they merely replace one stricture with another stricture.

It is merely a different person, one of “us”, but holding a whip just as painful and now in the garb of an elite. Nigeria can be like the EU and its proto-states, the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman I’ve mentioned, and I cannot in any honesty support the creation of Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia. And, further back, I would rather have an Austria-Hungary than a Yugoslavia but a Yugoslavia is still much preferred to what happened after its disintegration into nationalist agitations.

Europe has known a long and violent history of secessionism. Catalunya and the Basque regions of Spain, Northern Ireland, to name but a few. In the late sixties, the Western public heard of the ‘Biafra war’; a war fought between the central Nigerian government and the secessionist Biafrans. It featured on TV broadcasts and made newspaper headlines, all accompanied by gruesome pictures of death and destruction. The Western audiences were made to understand that it was an internal Nigerian affair. Is there a possibility that the Biafran war of the late sixties has some relationship with the current drive for secession?

At the heart of today’s Biafra struggle is a curious type of xenophobia and the intellectualization of it.

I think xenophobia has always existed, I think it is this same xenophobia that led Igbo military officers to murder their fellows and the political leadership of the north and west in January 1966. A certain elite disaffection that interpreted itself in ethnic nationalist terms in a putative nation-state. This same xenophobia is what informs the press-ganging of parts of the country that were never even part of the 1960's separatist state, and parts that were and today do not care for it, into a Biafra that is essential, if we are to be blunt, an Igbo-ethnic state. How do you force people into your Biafra? Beyond that, how do you build a viable state based on ethnic xenophobia?

The intellectualization of this xenophobia comes from a sadder and more sympathetic place—that the Nigerian Federal state has failed its people, in terms of all the indices that a government is meant to provide, health, education, opportunities, and so on.

So, the question goes, if their “we” had been left to be in the 1960s, might things not have turned out better for the Igbo Biafran sought-to-be nation? Being aware of the serial failings of Nigeria, it is hard to counter this argument except that it is speculative and we will never ever know for sure. One can say that, considering there have been Igbo-led states in a 36-state federal Nigeria, which have enriched their own elite at the expense of their people, as is the overall Nigerian pattern, the premise of this speculation is very tenuous. But, who knows for sure?

In Europe, the secessionist movements not only resorted to political action, but also to terrorism. Now it must be said that what is deemed ‘a terrorist’ to one may be considered ‘a freedom fighter’ to others. It is all a matter of perspective. What is your perspective? Should the current spate of Biafran agitation be regarded as terrorism?

At present, the Biafran agitation is merely a threat to Nigeria’s internal security. However, the then leader of the Radio Biafra/Independent People of Biafra (IPOB) movement that gave expression to this current agitation is on record asking Igbos in the diaspora to contribute arms to his organization in order to launch a military-type agitation. He has personally woken up the latent curious xenophobia that exists in southeastern Nigeria with his own virulent hate speech and extremism.

Arrested on arrival in Nigeria by Federal authorities, he was held and then arraigned for God knows what reason for a treasonable felony when the Federal Government could have gone for a treason conviction ab initio. Being charged with a felony, the issue of his bail became another source of heating up the Nigerian polity, which some of us see as a deliberate action by elements of the government to aid Nnamdi Kanu, make him some sort of factor in Nigerian politics. He was eventually granted bail, and promptly resumed his hate speech, and entered political territory by placing an embargo on an election to be held in a state in the southeast. I think it was at this point that any tacit support he had amongst the Igbo political and intellectual elite floundered.

Following an altercation with the military, who were carrying out a show of force in the southeast, Kanu has not been heard from and did not attend his last court sitting. In the intervening period, he has been sacked by the Radio Biafra outfit for embezzling millions of dollars of the outfit’s funds. These funds seem to have come from contributions from people who believed his propaganda but what emerges now is that he is merely another criminal huckster who, playing on basic human psychology and latent curious xenophobia, has built a fortune on the gullibility of regular people and absconded with a pile of cash, his con complete. People like these, I think Nigeria’s internal and state security architecture, and the justice system, can deal with.

But, there is disenchantment with the way Nigeria has failed its promise.

Huge sections of our population live on less than two dollars a day. We have seen Abubakar Shekau and his predecessor sway thousands with the violent extremism rhetoric of Boko Haram, we have seen even Kanu and IPOB’s success in whipping up sentiments. Now, what happens when a Fidel Castro or Che character shows up, committed, shrewd, and intelligent and at the right historical time? What if such a person believes in using the tool of terrorism and is able to rouse the lower classes who have gotten a really raw deal from Nigeria and who number in the hundred million? This is what scares me. Would such a person not, in fact, be a “freedom fighter”?

This is why while I am against separatism, I am also staunch in insisting that a multi-ethnic Nigeria must be intelligently built, one that shuns sentiment over merit, for which each and every citizen regardless of what part of Nigeria they were born, their ethnicity or their religion, has the greatest chance of achieving self-realization and accessing opportunities. Only then can we correctly counter separatism of the basic ethnic or chauvinist sort.

Do you think the Biafran agitators are realistic in their quest for independent existence from Nigeria?

No, I don’t. For the reasons, I have outlined. It won’t happen, but it will create needless problems for the country. At the center of the issue for separatism is the issue of legitimacy. No state willingly gives up its legitimacy.

It is next to impossible to argue the thin line between creating a nation-state out of one that already exists and questioning the right and reality of the first nation-state existing. I think there are more effective ways to pressure states to act in certain ways. Polarizing agitations, whether or not they devolve to the use of terrorist methods, are not helpful if it is the improvement of the lives of ordinary people that is really the issue.

Maybe more important even; is their cause just? Europe has a long and bloody history of nation-building. Yet this always has been a European affair. Most of Africa‘s boundaries were drawn up on a map by colonial rulers, as was the sovereign state of Nigeria.

Their cause is not just. What is here is a mish-mash of ideas that are satellites around very recent notions of identity. Throw in an unscrupulous elite. Throw in chauvinism or xenophobia. Throw in the idea of a nation-state and nationalism. Throw in a youth bulge. Throw in the problems of globalization at the local level. Have largely pre-modern people wearing the masks of modernity. And you will have disruptions such as this.

I consider myself to be an African, I hold a West African passport issued by ECOWAS [Economic Community of West African States]. I will ditch this passport as soon as the African Union starts issuing the new African passports. I refuse to privilege colonial creations like Nigeria and Kenya and Cameroun to the extent that they exclude me from people from whom I suffered the shock of slavery and colonialism and neocolonialism. I reject this.

I am devoted to the idea of multi-culturalism within today’s colonial created states within a larger framework of African identity which is, perforce, multi-cultural. I am pan-African.

I have based this identity on five centuries of interference and treachery by the West. I am from a really huge Island called Africa and while, yes, it is true, that I need visas to visit some parts of this continent, this is changing. I feel at home in Kigali as I do in Abuja, and I love Mombasa just as I love Zanzibar or Jos and it would be easy for me to be local in these places.

As in the case with Catalunya, don’t you consider that a referendum could and should be decisive at this point on the matter of secession?

I’ve said it before that the southeast should be given a referendum on whether they wish to stay in Nigeria or not. That, for me, would be self-determination. It would solve the problem neatly, to my mind. But, there are two 'buts'.

First, there is the question of who would organize such a referendum and what its effect would be. Nigeria will not cede its legitimacy to the United Nations or anyone else to conduct a referendum, and this crucial point will see the proponents of a putative Biafra reject the referendum no matter how it goes. So, what would have been the point?

Personally, I do not see how the separatists can carry a referendum on the secession of the southeast from Nigeria. We have grown too strongly interrelated that I think most Igbo people when the question is put in stark terms, would rather stay in Nigeria where they have huge investments already. Be that as it may, if the referendum is carried, they should be allowed to go but those Igbo people who opt for Nigerian citizenship should be allowed to take it up exclusively.

How would this work in practice if, following a referendum carried by the separatists, Nigeria grants the will of the separatists and promptly closes its borders and trade with the newly independent Biafra? How would the Igbo who take up Nigerian citizenship feel about this? At what point in all this will their loyalty to Nigeria be tested, how will their fellow Nigerian citizens feel? Do you see why a responsible Nigerian government will find this position untenable?

So, Nigeria is damned if it does and damned if it does not on the issue of a referendum. I do not know enough of the Spanish situation to say if this is a similar problem Madrid is having beyond the concessions already given to the Catalans.

Recently there have been disturbing reports, - as we have also reported on at least one such account - with graphically detailed evidence available on social media, of (para-)military actions taken against Biafran protestors; evidence of human rights violation. We have read reports on the part of the Nigerian government in which said events were discarded as fake news. Which is hard to believe from our perspective. What is your perspective?

I think there has been a thorough propaganda war, on the one hand, led by those sympathetic to the separatists. On the other hand, Nigeria’s security forces do not seem to have thoroughly understood the type of asymmetric war that is going on.

A lot of these are indeed fake news meant to rally the faithful around a separatist banner. But where a single policeman shoots a live round into a kid’s head and you have his sister or mother inconsolable, how can you explain it away?

The Nigerian security services need to be more intelligent in dealing with separatism. It’s an asymmetric terrain and hard approaches will yield nothing except the hardening of stances. This is why I say the solution lies in sustainable economic growth and the expansion of the existence and access to opportunities while providing healthcare and roads and the very basics of development. This takes the wind to clear out of the sails of any separatist ship.

Again by means of comparison in the case of the recent upheaval in Catalunya, the central Spanish mishandled the situation regardless of the fact that they acted within the legal boundaries of their constitution. They misbehaved from a humanitarian perspective. In your view, how would you rate the Nigerian government’s handling of the Biafran issue?

I’d rate the Nigerian government’s response to Biafra exactly as I rate its provision of social services the basis of development and the expansion of opportunity. Very much below average. Very unhelpful in addressing the problem at hand.

Key motivators for Catalunya’s recessionary drive are economic and monetary in nature. Catalunya is a prosperous region of Spain that pays more taxes than it receives in benefits from the central government. How would you assess the situation in Nigeria in this light? What does Nigeria stand to gain economically if remaining a functional whole? Could there be a possibility that the Biafrans be convinced to dissolve their agitation and remain with Nigeria proper?

This is also one of the problems with Biafran separatism. Even the most optimistic proponents of it premise it on potential. Potential, not on anything tangible.

I am thoroughly distrustful of stereotypes but the stereotype of the Igbo people is that they are excellent, even genius, business persons. This is informed by the fact that, for some reason, the very best and the brightest of this type of Nigerian, the Igbo businessperson, is found in numbers everywhere in Nigeria except the Igbo heartland itself.

From Zuru to Yola to Ore. And this class of business person has thrived and gotten the fruits of success in business. But they have not escaped from the Nigerian reality of existing and thriving within an economy heavily reliant on the extraction of petroleum from the Niger Delta. As with the north, I have not seen a single stirring of the sort of macroeconomic strategy and policy that can create value to sustain putative Biafra.

The insistence of the separatists in including the oil-producing areas of the Niger Delta into an imagined Biafra is based on the imagination of these separatists not extending beyond the client-patronage rentier type corruption that typifies Nigeria’s economy today in their Biafra. So, what exactly are they about? Beyond xenophobia, there is no purpose beyond replicating another Nigeria in the southeast with a new class of people with greater access to the public treasury. Where they maybe get 20% in Nigeria, they’d had 100% in a Biafra.

There is no articulation of any way to learn from Nigeria’s mistakes and avoid its fate. Most of the money spent in the southeast, as in all the other regions of Nigeria, comes from Federal handouts in the form of constitutionally guaranteed allocations the bulk of which comes from the extraction and environmentally degrading activity in the Niger Delta. Internally generated revenue profiles do not lie, pick anyone from any part of the country and compare it to what the Catalonia region generates for Spain.

If Catalonia has a fiscal case for its separatism, Biafra has none.

Another driving factor for the Catalunyan secessionist movement is a cultural divide. Catalunyan language and culture are very distinct from the Spanish mainstream culture. Nigeria is even more culturally diverse than Spain (and many other countries for that matter). It seems there is a glaring level of distrust amongst the component nations of Nigeria. One only has to follow up on discussion threads on social media to see for themselves. How did this level of mutual distrust come about? And is there a possibility for a recovery from this state of affairs?

It is a failure of leadership. We have coddled an elite that thrives on rent and nepotism, who sell dummies of excuses to their constituents. We have politicians who cannot be held accountable because the people have conditioned, bought into various narratives of and “us” against, necessarily, a “them”. Whilst the people are thus distracted, the politicians are not held to account in terms of roads, hospitals, and jobs. Put that on one end of the table.

Then on the other end, but the youth bulge who have been given a poor quality education that prepares them for nothing at all, not even for opportunities that do not exist. A lot of what you see on social media is angst, it is driven by kids who do not know anything about anything, who imagine that Civil War is a joke and that bullets are easy to deal with anywhere other than in sentences and accounts.

This, in turn, is why it’s such a dangerous situation. I had hopes that the Buhari administration would proactively deal with this issue of national identity based on the coalition of interests it came to power with. In its early days, I advanced the idea of a “post-ethnic youth” in an essay published in New York. That optimism is long outraged, long gone.

If Biafra does have her way with an independent existence from Nigeria, what does it portend for the rest of Nigeria? Will it possibly have a domino effect on the remainder of the country? This is at least a soft-spoken fear amongst European leaders.

You must imagine five to ten civil wars breaking out in what was once Nigeria. It’s as simple as that. It’s not just European leaders who have this fear. It’s anyone who has a brain really, with the exception of the pan-ethnic Nigerian elite who are so far gone in their corruption as to be unable to see that they are now at risk of losing everything.

The issue of Biafra is one of many cases of restiveness plaguing countries of West Africa. But it is evident that ECOWAS is yet to live up to its full expectations in policing the sub-region. What do you consider to be the reason for this?

As a somewhat undiplomatic Nigerian diplomat was heard to say, “16 minus 1 is 0”. Nigeria’s population, at 170 million-plus, is well over half of the entire economic bloc’s population. Key institutions of ECOWAS—the secretariat, the parliament, and the regional court—are in Nigeria. Nigeria foots most of the bills. When the situation in the Gambia occurred, it was Nigeria that put a fleet to sea to persuade Jammeh to behave. There are just some things that only Nigeria can do, even in an ECOWAS where all states are equal. Do you see the International Criminal Court issuing a warrant for George Bush or Tony Blair? I don’t see it.

Same way, policing ECOWAS can only be done with Nigerian buy-in. What do you think will happen if that same Nigerian government, controlled by the corrupt Nigerian elite, imagines such policing is aimed at them? There will be no cooperation. Every one of those 15 other heads of state prays Nigeria sorts out its internal security issues because they will be unable to stanch the flow of Nigerian refugees in the immediate sub-region if the integrity of the Nigerian state collapses.

Every ECOWAS head of state knows too that their infrastructure can only absorb or repress a fraction of potential Nigerian refugees, and they know what Nigerians can do when they have their backs to the wall. No one wants this. We in Nigeria do not want this either. ECOWAS is an economic bloc and is still in the process of integrating itself. It is on the right track but it will be a decade yet before it can wield power the way say Brussels does in Europe today. Maybe more.

On the intellectual front, what effort has been done to remedy the situation? Or do you think that the intellectual circle has fallen onto different sides of the Biafran divide? If so, how big of a divide is this from an intellectual point of view?

Intellectuals without political power are not of very great use in an irrational society.

This is the situation of the Nigerian intellectual elite, an emasculated position. So, we have the untenable situation where some intellectuals turn themselves into sectarian activists because that is the only way they will be listened to. You must agree this is an untenable position. The whole point of being an intellectual is to be independent of the times, to look at it with a clear and considered eye, to be in fact, disagreeable, often than not.

I locate the point of the decoupling of intellectuals and their relevance in Nigerian society to the mid-80’s when the West very helpfully conned third world countries into undertaking “structural adjustments” that decimated the middle classes at the same time chiliastic Pentecostalism and Wahabism were coming in to capture the reason of the middle and working classes now thrown into insecurity and crises. Those who survived did so by abjuring their voices or becoming taffeta thinkers in the service of functionaries of various regimes. As they did this, they lost their power. Today, they write pieces no one reads, except when they say what their readers want to hear.

To your question, regardless of my pessimism, I try. And we still talk across these false divides. At the height of the virulent ethnic hate speech of IPOB and Nnamdi Kanu, I was pleased to sign a Statement of Concern on the rise of Ethnic Hate Speech along with other Nigerian writers.

The idea of the Statement was Nwachukwu Egbunike’s and he got us all together from across the country and the diaspora to endorse and issue this statement. Nwachukwu is from the southeast, I am from central Nigeria, thinkers and writers from all across the country viewed this issue with grave concern. Our statement was carried in the media but ignored by the government and, of course, by IPOB. I do not think it changed anyone’s mind on anything. But it was put out there. There are those of us who are concerned, who argue for nuance and intelligent engagement. But we are both in the minority and do not have much power.

Thank you so much Richard for taking the time with us. This interview has turned out to be a lengthy but very interesting read from your perspective. We’ll be looking forward to new publications from your side. Please keep us posted as we will inform you.

Richard Ali was shortlisted for the John la Rose Short Story Competition (2008). He has participated in various writing workshops including the 2012 Farafina Trust Creative Writing Workshop and the 2013 GRANTA/British Council Workshop.

Richard has served as Judge for the BN Poetry Award [Africa’s only Africa-wide poetry prize] and Rwanda’s Huza Press Short Story Prize and has been a Guest at several Festivals across the continent. He sits on the board of Uganda’s Babishai Niwe Poetry Foundation and is a member of the Jalada Africa, a writer’s collective, based in Nairobi, Kenya. "City of Memories", his first novel, which borders on the question of identity, was recently reissued by Parresia Books.