Abubakar is a Nigerian writer and journalist. He is the author of the novel Season of Crimson Blossoms and the short story collection, The Whispering Trees. A 2013 Gabriel Garcia Marquez Fellow and 2015 Civitella Ranieri Fellow, he was shortlisted for The Caine Prize for African Writing, 2013 and won the BBC African Performance Prize, The Amatu Braide Prize for Prose. He is also listed in the Hay Festival Africa 39 list of the most promising sub-Saharan African writers under 40. He writes for the Daily Trust newspaper in Abuja.

Dear Abubakar, thank you so much for your time and the privilege of conducting this interview with you.

Thank you. It is a pleasure.

Let us start of by asking you first about the state of affairs with Nigerian fiction writing. In the sixties, the reading public looked to Nigeria for their supplies of African fiction. Outstanding works were coming from the country, and there was hope. The case is not the same today. A few books get to the reading public now and then; but only a very few. From our perspective, Nigerian writers find it hard nowadays to get their work known amongst the general public both at home and abroad. What happened to the Nigerian industry for fiction books? (and non-fictional book publishing for that matter) What is your assessment?

What happened was there was a break in the production chain. The structures that made that early literary explosion possible failed as a result of several factors. The civil war interrupted that creative energy as the writers put aside their typewriters and went to war, either as soldiers or diplomats or pen warriors. After the war, they went back to write, some of them writing their war experiences. The recovery process was still on when the economy collapsed in the ’80s, causing the publishing houses to fold up.

So a generation of Nigerian writers in the ’80s and ’90s failed to find an outlet for their works through conventional means and had to resort to self publishing to get their works out. The downside was that they didn’t have the editorial support and the distribution chains to get their works across to a wide audience. Where these books were available, people had to make a choice between buying books and buying bread. Not a favourable position for all parties if you look at it critically. And when you consider that decades of military dictatorships took an anti-intellectual tilt, you understand why the collapse of the publishing industry was not mourned as the national tragedy that it was. It did not help in reviving the publishing industry. It is no coincidence that publishing in Nigeria is reviving after the military left the political sphere.

On the other hand, the film industry is making waves. Nollywood is being lauded globally for her growth. In spite of the odds the film industry players are succeeding in pushing the industry forward and maintaining its ranking next to Bollywood and even Hollywood. Are there lessons to be learnt here for the book publishing industry? What is your perspective as a writer?

The film industry operates an interesting model. It is mobile, dynamic and has managed to find mass appeal. They have adapted to the realities on ground. Most of the people who pioneered the industry were business men who saw a need for local content and decided to create them. They adapted to the realities in getting their works across to the audience. They realised, for instance, that the centre of piracy in Alaba Market has a huge distribution network and strong connections. They couldn’t be be curtailed through legal means because they have no qualms milking the corrupt system.

So what the film producers did was to liase with the pirates. They agreed to entrust them with distribution rights for a return of the profits. The business has grown and now you have skilled people coming in. Nollywood did not start off being intellectual. It went for mass appeal, for people who invest time and resources in procuring these movies. Now you have skilled people coming into the movie industry and trying to improve the standards with movies grossing highly in the cinemas.

With writing, you have to be honest and admit that there has been an intellectual arrogance that has characterised our operations.

This is not to exclude the fact that writing has had a long history and writers have had ways of doing things for centuries. It is not always easy to adapt the Nollywood strategy to writing, the cost of producing books is far more than what it takes to produce a movie DVD or CD. Books are more expensive, they are slower to consume than movies are. And writers, through no fault of their own, cannot go into the trenches as Nollywood producers have done. But the question one has to ask here is: is it the place of writers to go into the trenches and make these adaptations? Writers are writers and the business of selling books is that of publishers. The business models are different and the onus of adapting these to books is more on the publishers than on the writers.

Do you consider that creative arts could and/or should serve as a tool for securing social justice? In the present Nigerian situation, can it serve to bring about a peaceful solution to the multiple threats plaguing the political and geographical integrity of the country? Do you feel that writers have a special obligation with regard to this matter?

I believe that the creative arts should serve whatever purpose the individual creator intends it for. The creative arts has the capacity to serve all purposes, be it social crusade, entertainment, elightenment or purely as an artistic form of introspection. It is placing an unfair burden of expectation, most of the time on writers and it is often limiting on all the great things literature and other creative arts can be used for. My attitude to this question is that for those who fancy arts for the sake of art, let the art please them as they will. And for those who want to use arts for social causes so be it. There is room enough for all applications.

However, in Nigeria, most of the novels that have had the greatest relevance have always had some social issues at their heart. I don’t think this is a mistake. It is something to do with our approach to storytelling and the creative art, even in pre-colonial times when storytelling was a socialization tool, where most stories are, by default, expected to have some moral value. When modern Nigerian literature evolved in the 1950s they took on a social cause, the fight against colonialism and African’s right to identify as humans, it was principally to counter the negative narrative about the continent and its people. In that sense, it has become a tradition to turn to the arts to champion social causes.

It is curious that South Africans have a better understanding of the British than they do of the Nigerians.

Personally, I see the creative arts as a useful tool to create understanding between people, especially in a country as diverse as Nigeria, where perceptions of each other are mostly informed by handed-down stereotypes. When one looks at it, it is curious that South Africans have a better understanding of the British than they do of the Nigerians, and the Congolese have a greater understanding of the French than they do of the Gabonese. These are things that could be changed if people have more access to each other’s literature. So writers have a great role to play in the political and social sphere across the continent both as writers and citizens. At the same time we must not forget that there is so much more that writing can accomplish and it is fine if some writers don’t feel like championing causes and it is fine if they choose to.

Speaking of (social) causes; there is Boko-Haram insurgency in the North, Niger Delta militancy in the South, whilst the Biafrans in the South-East have been maintaining their bid for secession for decades. Is there an underlying cause for this multiple threats to the Nigerian political and geographical integrity?

The underlining cause is the lack of social justice and equity.

No system is perfect but the Nigerian system has been more flawed than most. And it is not necessarily the system or the idea of it that is flawed, because I believe Nigerians often are great at drawing up planning documents and policies. The greatest flaw in the system is the people, both those running the system and those who are supposed to benefit from it.

Principally, we have had the same set of people running the country for decades, practically since independence in 1960. These are people who inherited the flawed colonial structure that Nigeria was established on, not as a country but as a business enterprise for Britain. They inherited that system and as nationalists instead of modelling the system and fashioning Nigeria into a country, they maintained the status quo and continued running Nigeria as a colonial outpost that benefits only them and thier families and cronies. The same men who started the Nigerian civil war in their twenties and thirties are still running the country today in their seventies and eighties and have no intention of stepping aside.

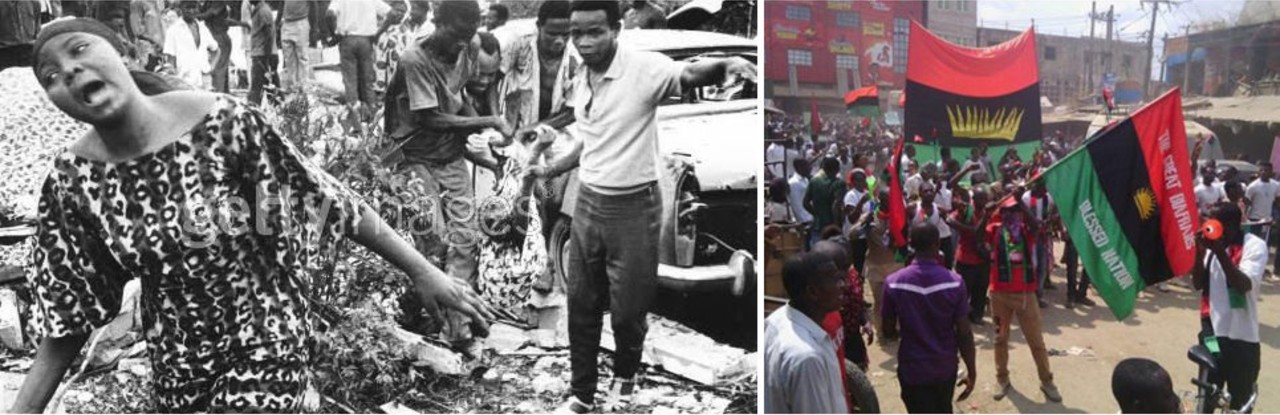

Young people have in most cases, shown an incapacity to take control of their destiny because they have been conditioned to scrap for the crumbs falling off the table of these so called leaders. The Biafran agitations are not without cause, people are angry and aggrieved, but unfortunately they have allowed some vested interest to exploit their anger for personal gains. The Biafran agitations is flawed, not because there is no injustice to the people of that region - because there are injustices being meted out to all peoples of Nigeria, from all parts of the country - but because the Igbo man, has more in common with the hustling Hausa man than he does with his Igbo kinsman in power, is now being exploited by some local tribal elements who want to corner a part of the country for their own gains.

Nnamdi Kanu is not fighting for the Igbo, he is fighting for himself.

He has set himself up as a demi god and has had naive Igbo youths worshipping at his feet while he robbed them blind. How different is he from the thieving politicians he is trying to fight? The same applies to the Boko Haram leaders. Who is Shekau fighitng for? What is he fighting for? He has succeeded in selling an impractical ideology to some people who are willing to give their lives for it. And then some people, politicians, government officials and the military, have found a way to profit from all these conflicts. They divert relief materials meant for displaced people. No matter what system you impose on Nigeria, unless Nigerians make the collective decision to make sacrifices and build a nation, these systems will fail. And as long as these social injustices persist, charlatans will always exploit gullible people in the name of fighting for their rights. It is a vicious circle.

Nigeria is not alone in this respect. We may observe on a global scale an increase of nationalist, ethnic and cultural movements that pursue their own agendas which often conflict with national and even supra-national interests. In this first rendition of our interview series we are seeking for similarities and disparities between what is happening in Africa - in this case Nigeria - and the affairs of many European nations operating within the framework of the EU. The EU is in a process of resolving the consequences of the ‘Brexit’ vote and has recently been faced with a failed referendum on Catalunya’s independence from Spain. Do you see similarities with for instance Boko-Haram’s islamist drive and Biafra’s longstanding secessionist claims?

There are differences and their are similarities. The differences are that Brexit was constitutional. People actually voted for it, even if a great majority of them did not understand what they were voting for. I think we credited the Brits with more social intellegience than is the case. The same thing could be said about America with respect to the emergence of Trump. In Catalunya they voted as well, even if the legality of that vote is being questiond by the Spanish government.

Who voted for Boko Haram?

When they raid your house and put a gun in your face, what option do they give you? The Biafran agitators demonstrated a lot of naivity and a lot of ignorance and worse a lot of hate for their fellow countrymen who are suffering as much as they are. What we fail to understand is that the true difference in Nigeria is not between the north and the south, it is between the people and those in power. It is like Orwell’s Animal Farm. The moment an Igbo man and a Hausa man and a Yoruba man get into power, they speak a new language, the language of those in power which excludes those being governed. When we realise this, we will have a better understanding of which direction to channel our anger.

Until then, charlatans like Kanu and Shekau and other ethnic and religious bigots will exploit the gaps and set people against each other for their personal gains. And it is easier now to do this because we are living in an age of protectionism, in which people want to hold certain contrarian ideas and protect them with all tools available to them in other to attract attention. It is a performance born out of a reality show mentality. People corner spaces on social media and set about performing life, performing love, performing anger and hurt, performing pregnancy.

Everything becomes a performance. You meet people who are perfectly normal and polite in real life, but once they get on social media they become angry imps and vixens because they realise they need that drama to attract attention to themselves. You don’t know what is real or not anymore. The rise of right wing tendencies and nationalism can be explained as a reaction. Often, conflicts such as the great wars have shaped how humans live. The world is changing. There is a conflict that many people are not aware of. The rise of increased liberties and extremism is being countered by increased nationalist and right wing tendencies. The mass movement of refugees is being countered by nationalism, a manifestation of the protectionism I referred to.

The world is changing, but this time the forces at work are not as clearcut as we knew from the past.

Is the Biafran exercise for independent existence from Nigeria proper achievable? How feasible is the emergence of an islamist ‘state’ in the North of your country?

I honestly don’t think so. Nigeria is bound by forces that cannot be explained by theorists. The people, despite their differences, have a lot more in common than they are actually think. Boko Haram does not have the support base or the capacity to create an Islamic state. All instances of this happening elsewhere in the world have failed: the Taliban in Afghanistan, IS in the Middle East. Nigeria is too complex for that.

The North is not singular. There are tribes and different religions in the North. The barbarity, such as the type demonstrated by Boko Haram, has never created and sustained a country. Biafra is a complex issue. A war was fought over this and hundreds of thousands of people lost their lives as a result of it.

Those who have forgotten the lessons of history are the ones championing another war.

At the time the [Biafran] war [1967-1970] happened, I think it is totally understandable that it did, even if I think it could have been avoided, you could understand the motivations of the warlords on both sides. But now, the situation is different. The injustice that the Igbo face is being faced by Nigerians in other parts of the country as well, irrespective of who the president is.

Within the EU, UK’s ‘Brexit’ economical secession is a reality, as Catanlunya’s drive for independence will be expressed in a second referendum. These are just two examples which an entity like the EU - not all that dissimilar in size, scale and complexity to Nigeria – is facing. If our assumptions with regard to the EU hold merit, then why wouldn’t they in the case of Nigeria? What is your take on this?

Brexit was born out of ignorance powered by misguided political brickmanship. The Catalunya agitation does not look any closer to becoming a reality than it was years before. It is a far more complex task. Catalunya is part of sovereign state and sovereign states are guided by international law and this laws are set up in a way that protects countries from losing chunks of their territories to internal agitations. Why these cases do not apply to Nigeria is that respect for the rule of law is far greater in the EU than in Nigeria, where the state has habitually defied court orders, where cases of blanket human rights abuses by security agencies are regularly swept under the carpet, where perpetrators of war crimes and mass murders in Jos, Kaduna and elsewhere have never been made to account for their crimes.

There is alleged evidence of human rights abuse in response to the Biafrans’ call for secession. All over social media platforms, disturbing images confront the senses of the viewing public. The Nigerian government maintains their denial of such allegations, deflecting from it as being ‘fake news’. Can you set the record straight on this?

Human rights abuses are unfortunately second nature to the Nigeria military, the police and other security operatives. The culture of brutality is deeply entrenched in them over decades of military rule that has cost them the good will of the people. Clearly there were cases of human rights violations as have been in other instances. There is no denying that. However, having said that, it is also clear that these cases were often exaggerated.

The Biafran lobby has had a history of having a strong propaganda machinery in place and some of the photos being circulated predated the recent crack down. Some of them were not even from the Nigerian case. But there is no denying that some rights abuses took place and such acts are totally reprehensible and the perpertrators ought to be brought to justice. Until the Nigerian military and police learn to treat the people they are sworn to protect with respect for their fundamental human rights, they will always have difficulties in doing their jobs. And until the law is brought into effect to bring human rights violators to jusitice, we will continue to have a disgruntled citizenry.

A good number of books have been written on the subject of the Biafran secession starting with the Biafran War forty years ago, up to today. To the best of our knowledge, most were written by Biafran writers, chronicling their victimization in the war and the years following after. Is there a possibility that these works of previous generations have contributed in propagating the drive behind the current secessionist activism?

The Biafran narrative is a curious one. It has been said often that history is the account of the victors. But most of the accounts of the Biafran war has been written by people who one way or the other identify or sympathise with the Biafran cause, while the Nigerian, federalist account has been rare. I remember asking a key figure from the north during those times why they chose not to write about that period and he said they thought it was an unfortunate episode and that the country ought to move on. In retrospect, he admits this was a mistake. That mistake is costing us now because the narrative is unbalanced and people read one side of the story and come out screaming a great injustice was done. Fifty years onwards we have to address the same issues all over again. Our generation is now burdened with the mistakes of the past and this is unfortunate.

With respect to Boko Haram, one book, Holy Quran, is deemed as the inspiration and propagator of their ‘islamist’ ideology. The religion of Islam is considered a threat to society by European politicians like Le Pen, Wilders and DeWinter. How do you see this?

Human history is full of instances of people using religion to justify their perversion or reality and Boko Haram is no different.

It is true that Boko Haram has claimed the Qur’an as an inspiration for thier violent orgies. That cannot be denied. What is ironic is that figures like Ibn Khaldun, a forerunner in the the field of economy, sociology and demography, Avicenna, father of early modern medicine, the great mathematician Averroes, shaped the history of the world and they were influenced as well by the Islamic faith and so was Rumi, the great poet.

People have the propensity to misinterpret any text to justify their perversion.

People draw inspiration from faith, by the teachings of the Qur’an. People have the propensity to misinterpret any text to justify their perversion. The people who justified the trans-Atlantic slave trade and slavery did so by using the Bible. They used the Bible to justify racism. The caste system that has kept millions of people under subjugation in India is a product of the Hindu faith, it is entrenched in the religious text.

The man who shot John Lennon was inspired by the novel 'Catcher in the Rye' and the 1995 Tokyo subway gas attack carried out by some religious zealots was inspired by Isaac Asimov’s Foundation novels, they were inspired by science fiction. Justifications for perversions can be found anywhere. And people like Le Pen, Wilders and DeWinter draw the inspiration for their own versions of perversion, from a misguided nationalist sense and if you dig deep they are influenced by some kind of text, it could be Hitler’s Mein Kampf or something equally disturbing. The only difference between them and the likes of Shekau is that they have found more legitimate means of taking over state powers and using them to further their objective.

In your opinion, what can be done to engender peace and bring every component nationalities of Nigeria back to contributing earnestly towards her growth and development?

It is a tough question. Whatever is going to be done needs to start with justice and equity. Any society that is built on these principles will be a fair one.

With regard Nigeria’s growth and development, we have one question in conclusion. At UbuntuFM we are often faced with failing communications with our Nigerian contributors because of power outages. As we understand and experiencing it, this is a nationwide issue. How is it possible that an energy rich country like Nigeria is having these infrastructural problems? What is your assessment?

It is possible because corruption has been at the heart of everything going on in Nigeria. There is so much money in the power sector and people know this. Over the years, government has invested billions into rehabilitating the power sector but there is no account of this money and the job is never done. It is an avenue for some people to embezzle public funds.

At the same time there are business interests that don’t want this to be fixed because their business is importing generators, so they bribe people not to do their jobs. But at the same time, this is not all government. You have local agents who vandalise electrical installations for personal gains so this is a huge problem. They destroy what benefits the entire community so they can profit from it. So to say the failings is that of the government alone would be unfair.

It has been an insightful moment with you, Abubakar. Thank you for your time.

Thank you for yours too. Pleasure doing this.